d@art.info

"Accidents interest me, I have a very queer mind you know.

What fascinates me is the people they attract. The patterns those people form, an atmosphere of tension when something's happened....

Where there's a quarrel there's always a crowd.... It's a great draw. A quarrel or a body." L S Lowry

Laurence Stephen Lowry (1887-1976) used to say that he simply painted what he saw, common everyday scenes, often of incidents that caught his attention.

His work as a rent collector with the Pall Mall Property Company in Brown Street, Manchester (a job which he kept for 42 years until his retirement in 1952),

provided him with a unique opportunity to wander through the streets and enter the homes of 'his people'. Here he talked to and grew to understand and appreciate them.

Many of his tenants, their homes and incidents in their lives ended up in his paintings, the images he witnessed as part of his daily routine being stored in his memory

and reproduced in his art. 'When he saw a sight that attracted him he would stop in his tracks and... sketch on any piece of paper that came to hand'.

Lowry lived and worked all his life in Manchester and neighbouring Salford, one of the largest industrial communities in the north of England.

The industrial revolution in the 19th century brought about a huge population exodus from the countryside into the cities by people seeking work.

The massive influx of people forced the labouring classes to live in slums; only the middle class could afford to live out of the city centre and commute.

Overcrowding was a key factor in the spread of diseases such as diphtheria and scarlet fever. The small houses could contain up to ten people, living in unventilated rooms.

Between the rows of terraced housing there were open drains and rubbish where children played, and water came from wells that were often polluted.

The poor living conditions, long working hours in the mills and low pay all contributed to the general ill-health of the population and the frequent spread of disease.

Lowry met such sights every day and they were reflected in his paintings.

THE FEVER VAN

The fever van was the colloquial term in the north of England for the ambulance that transported patients with infectious diseases, usually scarlet fever or diphtheria,

to the local isolation or infectious diseases hospital. These vehicles were in existence throughout the country from around 1910 to the 1950s and had various nicknames.

Helena M Thomas from Rainham in Kent remembers a trip in one in 1918:

"The Fever Cart was a frequent visitor to Rainham in the early part of the century and although we children held our noses as it went by; many of us became passengers in our turn....

I remember being bundled up in a red blanket and lain head to the front in the little cab. I was probably too ill to notice much of the journey...

but I do remember the bumps of what I thought was the horse kicking the cab by my head".

Scarlet fever and diphtheria, now almost eradicated in the UK, were common in the 1930s. Scarlet fever occurred mainly in children between the ages of 2 and 8,

spread by droplets from carriers and affected individuals. Despite sore throat, headache, and fever, with red spots in the mouth and on the body, children would

often continue to play with friends in the street and to mix with neighbours, allowing the disease to spread.

Diphtheria was likewise highly contagious, generally affecting the throat but occasionally other mucous membranes and the skin.

The disease is spread by close contact with a carrier or by contaminated milk. It was very tempting for certain families to conceal a case since, for example,

an outbreak on a farm could lead to a ban on the sale of dairy products and hence loss of income.

The principal treatment was isolation. Patients were taken from their homes and isolated in special fever hospitals for up to six weeks.

This allowed time for their own immune system to fight off the infection and limited the risk of contamination between patients and family.

Helena Thomas remembers the consequences of having scarlet fever/diphtheria at the time:

"The health inspector arrived at the house to fumigate the bed and the room I had occupied. I spent a month in North Ward (of Keycol Hill Isolation Hospital)

and my mother was allowed to stand on a chair outside the window and see me in bed on Sunday and Wednesday afternoons".

The fever van symbolized the power of the medical officer of health, and was disliked and feared.

The presence of a fever van in the street meant that a child would be forcibly taken from the family, with a strong likelihood of never returning,

such was the high mortality of scarlet fever and diphtheria. Moreover, there were more materialistic concerns.

The disinfection procedure that followed the removal of the child was likely to have a very destructive effect: "The child's books and toys were to be destroyed,

its bedroom disinfected by the application of concentrated solutions of powerful germicides to the floor, bed, walls and furniture.

Wallpaper must also be stripped and burned". These procedures caused much disruption and discomfort for the household.

LOWRY'S PORTRAYAL

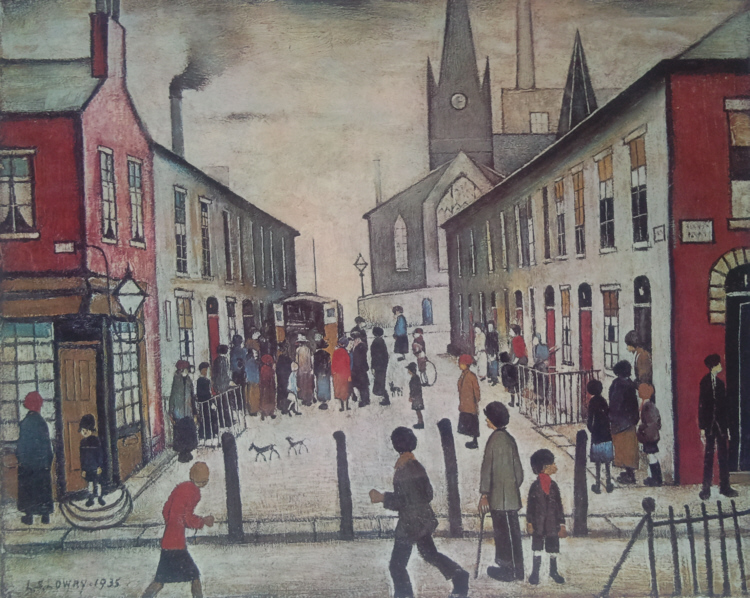

In Lowry's painting The Fever Van (1935) we can only see the back doors of a black cab that probably belongs to the branch of the ambulance service based at Ladywell Hospital,

the local infectious diseases hospital in Salford at the time. Subsequently all the ambulances in the area were brought together under a General Ambulance Service.

The ambulances based at Ladywell remained there, where disinfection facilities were available, until 1950.

The original painting; 'The Fever Van' (1935) by L S Lowry. (Reproduced by permission of the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool)

In this painting Lowry uses his typical palette of black, greys and red. These colours reflect the mood of the painting, with the terrace houses progressing from white

in the foreground to black towards the end of the row of houses and the fearsome ambulance. Hoyland described his use of colour as:

"... (using) almost pure black areas wherever imagery needs special emphasis".

This can be seen in the black mass huddled around the ambulance, emphasizing the gravity of the situation and focusing the viewer's attention on the concern being expressed

by the local community.

The layout of the picture makes a notable contrast with An Organ Grinder, painted the previous year. Both show a street scene with the two rows of terraced houses receding

into the distance. However in An Organ Grinder the focus is on life rather than death, with the people pausing for entertainment rather than for the event of a child being

taken away. They even have their back to a surgery that is clearly marked in the foreground; a building associated with illness.

There are church towers and mill chimneys in the background of both pictures, but much more prominent in The Fever Van.

The presence of the mill chimney perhaps offers a subtle indication of the root cause of the illness; the overcrowded living conditions of the mill workers.

The church suggests the unpredictable outcome of the child's illness: will it be the site of a thanksgiving or a funeral?

A noteworthy feature of both pictures is that the church clock has no hands; perhaps suggesting that life is so monotonous that time ceases to be important.

When Lowry painted The Fever Van his mother, a strong influence on his life, had been an invalid for some years.

It is possible that his constant contact with illness at home made him more sensitive to scenes of illness and desperation that he encountered in the squalid industrial

communities in which he lived. Did he use his paintings as a way to express grief and desperation? His disturbing self-portrait Head of a Man painted in 1938,

just before his mother's death, suggests that this was so.

The Fever Van, though probably influenced by the artist's state of mind, is based on the realities of the industrial North in the 1930s. From the painting,

we gain some inkling of the suffering endured by families touched by the curse of the van

These were years of isolation and growing despair, reflected in the paintings of Lowry. They depict derelict buildings and wastelands as mirrors of himself. As an official war artist - himself emotionally blitzed - Lowry drew the ruined shells of bombed-out buildings. In 1939, the year Mrs Lowry died - the person he most wanted to please - success came with the first London exhibition. "When the mother of Lowry died, all interest was lost, continuing to paint was the greatest salvation".

Just when this northern artist began to have success, Lowry was moving away from the subjects that everybody wanted him to produce. "If it were not for lonleness, none of my works would have happened". Some of the most powerful paintings by Lowry are deserted landscapes and seascapes. Some of the most difficult pictures to enjoy are of solitary figures and downs and outs. "These people affect me in a way that the industrial scene never did. They are real people, sad people. Sadness attracts me, and there are some very sad things. similar feelings in myself".

Everything came too late for Lowry, but the later years saw the British artist become a popular celebrity. Lowry also became preoccupied about whether his art would last. "Will I live", he asked over and over again, like the art of the Pre-Raphaelites Lowry collected and loved, "I painted from childhood to childhood". Lowry became an old man - often protesting to interviewers that he had "given up, packed it in".

LSLowry died aged 88 in 1976 just months before a retrospective exhibition of his paintings opened at the Royal Academy. It broke all attendance records for a twentieth century artist. Critical opinion about Lowry remains divided to this day. Salford Museum & Art Gallery began collecting the artist's work in 1936 and gradually built up the collection which is now at the heart of the award-winning building bearing the artist's name. Celebrating his art and transforming the cityscape again. A small quantity of paintings by the artist l.s. lowry were published as signed limited edition prints. Some of the most well known being, 'Going to the match', Man lying on a wall, Huddersfield, Deal, ferry boats, three cats Alstow, Berwick-on-Tweed, peel park, The two brothers, View of a town, Street scene.